Habitual tea consumption is associated with a lower prevalence of kidney stone disease in postmenopausal women

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- Stefano Menini

- Subject Areas

- Epidemiology, Nutrition, Public Health, Urology, Women’s Health

- Keywords

- Epidemiologic study, Cross-sectional study, Kidney stone disease, Menopause, Post-menopausal women, Tea

- Copyright

- © 2024 Wu et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits using, remixing, and building upon the work non-commercially, as long as it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2024. Habitual tea consumption is associated with a lower prevalence of kidney stone disease in postmenopausal women. PeerJ 12:e18639 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.18639

Abstract

Background

Menopause is associated with an increased risk of kidney stone disease (KSD). However, for postmenopausal women, how to avoid KSD has rarely been studied. The aim of this study was to explore whether drinking tea is associated with a reduction in the prevalence of KSD in postmenopausal women.

Methods

We collected 11,484 postmenopausal women from the Taiwan Biobank, and used questionnaires to obtain information on tea drinking, KSD, and comorbidities. The participants were divided into two groups according to habitual tea consumption: tea-drinking and non-tea-drinking groups. The association between habitual tea consumption and KSD was examined by logistic regression analysis.

Results

There were 2,035 postmenopausal women in the tea-drinking group and 9,449 postmenopausal women in the non-tea-drinking group. The mean age of all participants was 61 years. Compared to the non-tea-drinking group, the tea-drinking group had a significantly lower prevalence of KSD (7% vs. 5%). The odds ratio (OR) of KSD was lower in those who habitually drank tea than in those who did not (OR = 0.78; 95% confidence interval [CI] [0.63 to 0.96]) after adjusting for confounders. Moreover, postmenopausal women with a daily intake of two cups of tea or more had a 30% reduced risk of KSD compared to those who did not habitually drink tea (OR = 0.71, 95% CI [0.56 to 0.90]).

Conclusions

Our results suggest that habitual tea drinking may be associated with a reduction in the prevalence of KSD in postmenopausal women. Further studies are warranted to investigate the protective effect of tea on the development of KSD.

Introduction

Kidney stone disease (KSD) is a global health care issue, and the prevalence has increased in the past decades (Hesse et al., 2003; Scales et al., 2012). The high recurrence rate makes the disease a notable economic burden in many countries (Hyams & Matlaga, 2014; Uribarri, Oh & Carroll, 1989). A nationwide study in Taiwan reported that KSD affects more than 9% of the population (Lee et al., 2002). KSD may cause kidney injury due to obstructive nephropathy, leading to an increased risk of chronic kidney disease (CKD) or dialysis (Shoag et al., 2014). Hence, it is crucial to identify the risk factors for KSD.

Many factors have been reported to be associated with KSD in recent decades, including family history, personal history, cigarette smoking, secondhand smoke exposure, dehydration, hypertension, obesity, diabetes mellitus (DM), metabolic syndrome and diet (Baatiah et al., 2020; Chang et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2022; Siener, 2021). Male sex is also an important risk factor for KSD, and estrogen has been proposed to be a protective factor (Peerapen & Thongboonkerd, 2019). A large 2022 epidemiological study demonstrated that postmenopausal women had a higher prevalence of KSD, which provides a new perspective on the link between women’s health and kidney stones (Tang et al., 2023). Menopausal women have a large decrease in estrogen and consequently the protective effect of estrogen on stones is lost. Furthermore, postmenopausal women experience changes in bone metabolism, resulting in changes in urine composition. These two factors may explain why postmenopausal women have a higher incidence of KSD (Nih Consensus Development Panel on Osteoporosis Prevention D, Therapy, 2001; Prochaska, Taylor & Curhan, 2018).

Even though menopause in women and KSD are strongly related, few studies focusing have focused on finding ways to reduce kidney stones in postmenopausal women. One of the most widely discussed factors is postmenopausal hormone supplementation, however most studies have shown little protection against KSD (Maalouf et al., 2010; Mattix Kramer et al., 2003; Yu & Yin, 2017). Thus, there is an emerging need to identify protective factors for KSD in postmenopausal women.

Nutrition plays a crucial role in the prevention of KSD. Dietary patterns that include fruits and vegetables can lower the risk of KSD due to their high potassium and magnesium content, which helps inhibit stone formation (Ferraro et al., 2020). A low-sodium diet is also recommended, as high sodium intake can lead to increased calcium excretion in urine, heightening the risk of stones (Tang, Sammartino & Chonchol, 2024). Recent research highlights the beneficial effects of plant-based diets, which not only provide essential nutrients but also reduce the likelihood of KSD by promoting a more alkaline urinary environment (Zayed, Goldfarb & Joshi, 2023). Therefore, optimizing dietary habits is a key strategy in the prevention of kidney stones.

Tea consumption is recognized as a nutritional factor that may help reduce the risk of KSD formation. Previous cohort studies have reported an association between tea consumption and a lower risk of KSD (Barghouthy et al., 2021a; Ferraro et al., 2013). Numerous compounds in tea have demonstrated health-promoting properties, including antioxidant effects, which may provide a protective role against KSD (Barghouthy et al., 2021a; Ferraro et al., 2013). However, these studies have primarily focused on the general population, without specifically addressing postmenopausal women, who are at a higher risk for KSD. Therefore, we hypothesize that habitual tea consumption is associated with a reduced risk of KSD in postmenopausal women.

The present study aims to investigate the association between habitual tea consumption and the risk of KSD in postmenopausal women. Specifically, we seek to determine whether regular consumption of tea can lower the risk of KSD in this high-risk population. By utilizing a large-scale Asian cohort, we aim to provide insights into the potential protective effects of tea consumption against KSD and contribute to the understanding of dietary factors that may mitigate the risk of stone formation in postmenopausal women.

Materials and Methods

Study population

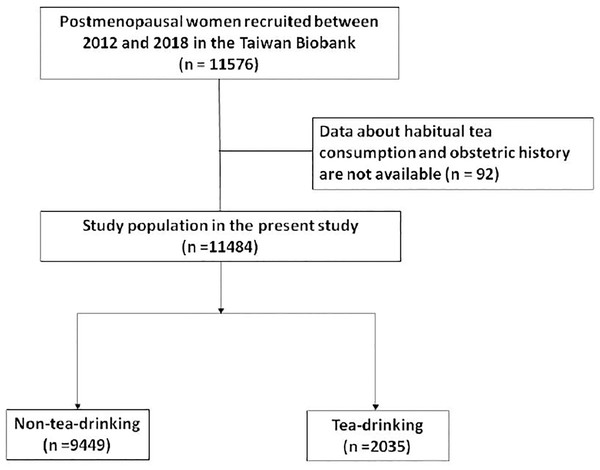

We recruited 11,576 postmenopausal women from the Taiwan Biobank (TWB), a large-scale population-based database. Data on volunteers were collected from 2012 to 2018. Detailed information about the TWB has been reported in previous studies (Chang et al., 2022; Chen et al., 2022; Huang et al., 2022). Participants without available data on habitual tea consumption and obstetric history (n = 92) were excluded, and the remaining 11,484 participants were included in the final analysis (Fig. 1). The participants were divided into two groups according to habitual tea consumption: tea-drinking and non-tea-drinking groups. Written informed consent was collected from all participants, and all investigations followed the Declaration of Helsinki. The Institutional Review Board of Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital (KMUHIRB-E(I)-20210058) approved this study.

Figure 1: Study participants were classified by habitual tea consumption.

Assessment of KSD

During standard visits, the participants were asked “Have you ever had kidney stones?”, and if so “When were you diagnosed with kidney stones?” through a questionnaire. The participants were also asked these questions during further follow-up interviews.

Assessment of habitual tea consumption

Questionnaires were used to assess tea consumption habits among the participants. Initially, the participants were asked “Do you consume tea regularly?” Those who answered yes were classified into the tea-drinking group, while the others were classified into the non-tea-drinking group. The tea-drinking group was then asked “How many cups do you drink per day?” and “Which type of tea do you consume?” The amount of tea consumption per day was classified as none, one cup per day, and at least two cups per day, and the type of tea was classified as fully fermented, semi-fermented, and non-fermented tea.

Statistical analysis

The characteristics of the participants were described using mean (standard deviation) for continuous variables and n (%) for categorial variables. To compare differences between the tea-drinking and non-tea-drinking, independent t and chi-square tests were used. We further utilized Cox regression analysis to estimate the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for the association between habitual tea consumption and the risk of KSD. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant and SPSS version 20.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) and R version 3.6.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Wien, Austria) were used to analyze the data.

Results

Clinical characteristics

Of the 11,484 included participants, the mean ages were 61 ± 6 and 60 ± 6 years in the non-tea-drinking and tea-drinking group, respectively. The participants who drank tea had a higher body mass index (BMI), higher proportion of cigarette and alcohol use, and tended to consume more coffee (Table 1). The non-tea-drinking group was more likely to have a higher daily fluid intake. There were no significant differences in the usage of hormone therapy or the etiology of menopause between the two groups. The tea-drinking group had a higher prevalence of DM than the non-tea-drinking group, while other comorbidities were similar.

| Characteristics | Non-tea-drinking group (n = 9,449) |

Tea-drinking group (n = 2,035) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 61 ± 6 | 60 ± 6 | <0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.8 ± 3.6 | 24.5 ± 3.5 | <0.001 |

| Smoke, ever, n (%) | 462 (5) | 147 (7) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol status, ever, n (%) | 224 (2) | 101 (5) | <0.001 |

| Physical activity, yes, n (%) | 5,459 (58) | 1,205 (59) | 0.235 |

| Married, yes, n (%) | 9,017 (95) | 1,959 (96) | 0.110 |

| Coffee, n (%) | 3,388 (36) | 1,031 (51) | <0.001 |

| Fluid intake (L/day) | 1,258 ± 565 | 1,129±649 | <0.001 |

| Hormone therapy use, n (%) | 1,920 (20) | 384 (19) | 0.144 |

| Menopause etiology | 0.766 | ||

| Natural | 7,778 (82) | 1,663 (82) | |

| Surgical | 1,610 (17) | 357 (17) | |

| Others | 61 (1) | 15 (1) | |

| History of hypertension, n (%) | 1,867 (20) | 440 (22) | 0.058 |

| History of dyslipidemia, n (%) | 1,443 (15) | 301 (15) | 0.608 |

| History of DM, n (%) | 786 (8) | 216 (11) | 0.001 |

| History of gout, n (%) | 109 (1) | 24 (1) | 0.919 |

| History of CKD, n (%) | 218 (2) | 40 (2) | 0.408 |

Note:

BMI, Body mass index; DM, diabetes mellitus; CKD, chronic kidney disease.

Habitual tea consumption was associated with a lower prevalence of KSD

In univariate binary regression analysis without adjustment, habitual tea consumption was associated with a 0.81-fold decrease in the risk of KSD (OR, 0.81; 95% CI [0.66 to 0.99]) (Table 2). After adjusting for potential epidemiologic parameters including BMI, smoking status, physical activity, hormone therapy use, history of hypertension, dyslipidemia, DM and CKD, the OR decreased to 0.78 (95% CI [0.63 to 0.96]) (Table 3).

| Parameters | Un-adjusted OR (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Age (per 1 year) | 1.00 [0.99 to 1.01] | 0.774 |

| BMI (per 1 kg/m2) | 1.04 [1.02 to 1.06] | <0.001 |

| Smoke, ever (vs. never) | 1.49 [1.11 to 1.99] | 0.008 |

| Alcohol status, ever (vs. never) | 1.30 [0.86 to 1.96] | 0.209 |

| Physical activity, yes (vs. no) | 0.83 [0.72 to 0.97] | 0.021 |

| Married, yes (vs. no) | 1.12 [0.76 to 1.64] | 0.563 |

| Coffee, yes (vs. no) | 0.86 [0.74 to 1.01] | 0.069 |

| Fluid intake (per 1 quartile) | 1.03 [0.96 to 1.10] | 0.406 |

| Hormone therapy use, yes (vs. no) | 1.20 [1.00 to 1.44] | 0.048 |

| Menopause etiology, surgical (vs. natural) | 1.18 [0.97 to 1.43] | 0.095 |

| History of hypertension, yes (vs. no) | 1.82 [1.53 to 2.16] | <0.001 |

| History of dyslipidemia, yes (vs. no) | 1.60 [1.33 to 1.92] | <0.001 |

| History of DM, yes (vs. no) | 1.73 [1.38 to 2.16] | <0.001 |

| History of gout, yes (vs. no) | 1.47 [0.81 to 2.67] | 0.209 |

| History of CKD, yes (vs. no) | 2.56 [1.79 to 3.67] | <0.001 |

| Habitual tea consumption, yes (vs. no) | 0.81 [0.66 to 0.99] | 0.045 |

Note:

BMI, Body mass index; DM, diabetes mellitus; CKD, chronic kidney disease; OR, odds ratio; CI, Confidence interval.

| Parameters | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Age (per 1 year) | – | – |

| BMI (per 1 kg/m2) | 1.04 [1.02 to 1.06] | <0.001 |

| Smoke, ever (vs. never) | 1.49 [1.11 to 1.99] | 0.008 |

| Alcohol status, ever (vs. never) | – | – |

| Physical activity, yes (vs. no) | 0.83 [0.72 to 0.97] | 0.021 |

| Married, yes (vs. no) | – | – |

| Coffee, yes (vs. no) | – | – |

| Fluid intake (per 1 quartile) | – | – |

| Hormone therapy use, yes (vs. no) | 1.20 [1.00 to 1.44] | 0.048 |

| Menopause etiology, surgical (vs. natural) | – | – |

| History of hypertension, yes (vs. no) | 1.82 [1.53 to 2.16] | <0.001 |

| History of dyslipidemia, yes (vs. no) | 1.60 [1.33 to 1.92] | <0.001 |

| History of DM, yes (vs. no) | 1.73 [1.38 to 2.16] | <0.001 |

| History of gout, yes (vs. no) | ||

| History of CKD, yes (vs. no) | 2.56 [1.79 to 3.67] | <0.001 |

| Habitual tea consumption, yes (vs. no) | 0.78 [0.63 to 0.96] | 0.021 |

Notes:

BMI, Body mass index; DM, diabetes mellitus; CKD, chronic kidney disease; OR, odds ratio; CI, Confidence interval.

Multivariable analysis adjusts for body mass index, smoke status, physical activity, hormone therapy use, history of hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease.

Association between the amount of daily tea consumption and prevalence of KSD

A total of 2,035 participants (18% of the study population) habitually drank tea, and 5% of this population developed KSD. After adjustments for confounders, daily tea consumption of two cups or more was associated with a 0.71-fold decrease in the risk of KSD (95% CI [0.56 to 0.90]) (Table 4).

| Daily cups* of tea consumed | No. of kidney stone disease/No. of subjects (%) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| None | 619/9,449 (7) | 1.000 (Reference) | – |

| 1 cup* per day | 24/322 (7) | 1.15 [0.75 to 1.76] | 0.525 |

| 2 cups* per day | 85/1,713 (5) | 0.71 [0.56 to 0.90] | 0.005 |

| Per 1 cup*/day | – | 0.86 [0.77 to 0.96] | 0.008 |

Notes:

OR, odds ratio; CI, Confidence interval.

Multivariable analysis adjusts for body mass index, smoke status, physical activity, hormone therapy use, history of hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease.

Association between the types of tea and prevalence of KSD

In terms of tea consumption, 16 out of 316 participants (5%) who drank fully fermented tea were diagnosed with KSD, while 93 out of 1,719 participants (5%) who consumed semi- or non-fermented tea also had KSD. In comparison, among participants who reported no tea consumption, 619 out of 9,449 (7%) were diagnosed with KSD. The consumption of semi- and non-fermented tea was associated with a 0.78-fold decrease in the risk of KSD (95% CI [0.62 to 0.98]) compared to the non-tea group. Although the fully-fermented tea group did not demonstrate statistical significance (OR: 0.76; 95% CI [0.46 to 1.27]) compared to non-tea drinkers, the overall trend in odds ratios remains consistent with those observed in the semi- and non-fermented tea group (Table 5).

| Type of tea | No. of kidney stone disease/No. of subjects (%) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| None | 619/9,449 (7) | 1.00 (Reference) | – |

| Fully-fermented tea | 16/316 (5) | 0.76 [0.46 to 1.27] | 0.296 |

| Semi- or non-fermented tea | 93/1,719 (5) | 0.78 [0.62 to 0.98] | 0.034 |

Notes:

OR, odds ratio; CI, Confidence interval.

Multivariable analysis adjusts for body mass index, smoke status, physical activity, hormone therapy use, history of hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease.

Association between habitual tea consumption and KSD by the type of menopause

In the analysis of the etiology of menopause, the tea-drinking group with natural menopause was associated with a 0.76-fold decrease int the risk of KSD (OR, 0.76; 95% CI [0.60 to 0.96]) (Table 6). After adjusting for potential epidemiologic parameters in multivariate logistic regression analysis, the OR decreased to 0.75 (95% CI [0.59 to 0.95]). In comparison, there was no association between drinking tea and KSD in the participants with surgical menopause.

| Postmenopausal hormone use | Un-adjusted OR (95% CI) |

p value | Multivariable OR (95% CI) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women with natural menopause | ||||

| Non-tea-drinking group | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| Tea-drinking group | 0.76 [0.60 to 0.96] | 0.024 | 0.75 [0.59 to 0.95] | 0.017 |

| Women with surgical menopause | ||||

| Non-tea-drinking group | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| Tea-drinking group | 1.03 [0.66 to 1.60] | 0.893 | 0.90 [0.57 to 1.41] | 0.638 |

Notes:

OR, odds ratio; CI, Confidence interval.

Multivariable analysis adjusts for body mass index, smoke status, physical activity, hormone therapy use, history of hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease.

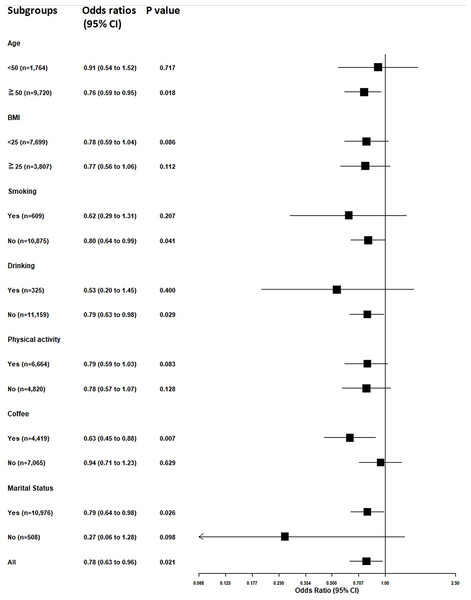

Association between habitual tea consumption and KSD in subgroup analysis

To address baseline differences between tea-drinking and non-tea-drinking groups, specifically in smoking status, alcohol use, and physical activity, which differ with p value < 0.001, we conducted a subgroup analysis examining the association between tea consumption and KSD in postmenopausal women (Table 7 and Fig. 2). Among postmenopausal women aged 50 and older (n = 9,720), tea drinkers demonstrated a significantly reduced risk of KSD compared to non-tea drinkers, with an OR of 0.76 (95% CI [0.59–0.95]; p value = 0.018). In nonsmokers (n = 10,875), tea drinking was similarly associated with a significantly lower risk of KSD (OR: 0.80, 95% CI [0.64–0.99]; p value = 0.041), as was the case in nondrinkers (n = 11,159; OR: 0.79, 95% CI [0.63–0.98]; p value = 0.029). In addition, coffee drinkers (n = 4,419) who consumed tea had a significantly reduced risk of KSD (OR: 0.63, 95% CI [0.45–0.88]; p value = 0.007), as did married individuals (n = 10,976; OR: 0.79, 95% CI [0.64–0.98]; p value = 0.026). These findings suggest a lower prevalence of KSD among tea drinkers in specific subgroups, particularly older women, nonsmokers, nondrinkers, coffee drinkers, and married women, supporting the hypothesis that tea consumption itself may play a role in reducing KSD risk.

| Subgroup | Odds ratio (95% CI)* | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| <50 (n = 1,764) | 0.91 [0.54 to 1.52] | 0.717 |

| ≧50 (n = 9,720) | 0.76 [0.59 to 0.95] | 0.018 |

| BMI | ||

| <25 (n = 7,699) | 0.78 [0.59 to 1.04] | 0.086 |

| ≧25 (n = 3,807) | 0.77 [0.56 to 1.06] | 0.112 |

| Smoking | ||

| Yes (n = 609) | 0.62 [0.29 to 1.31] | 0.207 |

| No (n = 10,875) | 0.80 [0.64 to 0.99] | 0.041 |

| Drinking | ||

| Yes (n = 325) | 0.53 [0.20 to 1.45] | 0.400 |

| No (n = 11,159) | 0.79 [0.63 to 0.98] | 0.029 |

| Physical activity | ||

| Yes (n = 6,664) | 0.79 [0.59 to 1.03] | 0.083 |

| No (n = 4,820) | 0.78 [0.57 to 1.07] | 0.128 |

| Coffee | ||

| Yes (n = 4,419) | 0.63 [0.45 to 0.88] | 0.007 |

| No (n = 7,065) | 0.94 [0.71 to 1.23] | 0.629 |

| Married | ||

| Yes (n = 10,976) | 0.79 [0.64 to 0.98] | 0.026 |

| No (n = 508) | 0.27 [0.06 to 1.28] | 0.098 |

| All | 0.78 [0.63 to 0.96] | 0.021 |

Notes:

CI, Confidence interval.

Figure 2: Subgroup analysis of the association between tea consumption and kidney stone disease in postmenopausal women.

Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) are presented for various subgroups, including age, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, drinking status, physical activity, coffee consumption, and marital status. The analysis adjusts for potential confounders such as body mass index, smoking status, physical activity, hormone therapy use, and history of hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and chronic kidney disease. Statistically significant associations are indicated by p values less than 0.05.Discussion

In this cross-sectional study of a population-based database in Taiwan, habitual tea drinking was significantly associated with a reduction in the prevalence of KSD in postmenopausal women. We also found that daily tea consumption of two cups or more was associated with an almost 30% decreased risk of KSD after adjusting for covariates. Among the different types of tea, semi- or non-fermented tea was more effective in reducing the risk of KSD. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first large-scale study to demonstrate a possible effect of tea consumption on the development of KSD in postmenopausal women.

Previous large-scale studies have reported that tea consumption was associated with an 8~11% lower risk of KSD (Barghouthy et al., 2021a; Curhan et al., 1998; Ferraro et al., 2013). The caffeine in tea has a diuretic effect, and it was shown to reduce calcium oxalate (CaOx) crystal adhesion on the surface of renal epithelial cells in an in vitro study (Peerapen & Thongboonkerd, 2018). Tea consumption has been associated with additional water intake. Moreover, the presence of antioxidant components may have a protective effect against stone formation (Itoh et al., 2005). Even though tea is known to contain oxalates, the amount of which is determined by the duration of infusion and type of tea, there is no evidence of oxalate-dependent stones in daily green tea drinkers (Rode et al., 2019). In female, the prevalence of KSD increases with age (Scales et al., 2012). In particular, postmenopausal status is associated with a higher risk of developing KSD, which may be due to differences in urine composition compared to premenopausal women (Prochaska, Taylor & Curhan, 2018). Shu et al. (2019) reported that tea consumption in middle-aged women was associated with a lower risk of KSD, predominantly driven by green tea, which is a non-fermented type of tea. However, they did not state whether their population included postmenopausal women. In the present study, we enrolled more than 11,000 postmenopausal women and collected sufficient clinical information to allow us to adjust for potential cofounders. The large sample size and detailed characteristics allowed us to investigate the relationship between tea consumption and the incidence of KSD.

In a previous meta-analysis, dose–response information was found in three studies (Dai et al., 2013; Ferraro et al., 2013; Goldfarb et al., 2005), and a daily intake of around 250 mL was found to be a cut-off level for the protective effect of tea consumption. Considered as a continuous variable, dose-dependent tea consumption (each 110 mL/day increase) has been associated with a reduction in the risk of KSD (Xu et al., 2015). Another study of 13,842 Taiwanese patients revealed that daily tea consumption of ≥240 mL (two cups) and ≥20 cup-years was related to a lower risk of KSD (Chen et al., 2019). Our results are compatible to previous studies of daily tea consumption. Taken together, these findings suggest that clinicians could inform postmenopausal women to drink two or more cups of tea per day to prevent the development of KSD.

Interestingly, we found that drinking semi- and non-fermented tea decreased the odds of KSD. Two longitudinal studies also found a decreased risk of developing KSD in people who drank non-fermented tea (Barghouthy et al., 2021a; Shu et al., 2019). Aside from additional water intake and the diuretic effects of caffeine, antioxidant compounds may play an important role in effect of non-fermented tea and in particular catechins (Henning et al., 2004; Itoh et al., 2005; Kanlaya & Thongboonkerd, 2019). In an animal model, the catechin epigallocatechin gallate was shown to have an inhibitory effect on urinary stone formation (Jeong et al., 2006). A Korean study reported that non-fermented tea contains higher concentrations of catechins than fully fermented tea (Jin, Jin & Row, 2006). This finding is consistent with our study, where semi- or non-fermented tea was associated with a decreased incidence of KSD. Regarding fermented tea, the small number of events in the fully-fermented tea group, only 16 cases of KSD, limits the ability to reach statistical significance. More research is needed to explore the role of fermented tea.

Postmenopausal status has been associated with a higher risk of developing KSD, and surgical menopause has been associated with a relatively higher risk than natural menopause (Prochaska, Taylor & Curhan, 2018). In an animal model, increased oxidative stress was detected in ovariectomized animals (Muthusami et al., 2005). Oxidative stress due to reactive oxygen species can cause oxidative damage to cells, and oxidative stress and CaOx crystallization have been strongly associated with KSD (Chaiyarit & Thongboonkerd, 2020; Khan, 2013; Li et al., 2021). Even though tea consumption can decrease oxidative stress, it had a limited effect in the women with surgical menopause in the present study, which may be related to higher oxidative stress. Hence, aside from drinking tea, high antioxidative dietary supplements for women with surgical menopause are suggested.

In our subgroup analyses, we demonstrated that the protective effect of habitual tea consumption was more pronounced in specific subgroups, particularly among older women (aged 50 and above), non-smokers, non-drinkers, coffee drinkers, and married women. This sensitivity analysis strengthens our conclusion that tea consumption is significantly associated with a reduced risk of KSD in postmenopausal women. These findings offer valuable insights into the lifestyle factors that may influence KSD risk and can serve as a foundation for further research in this area.

In summary, the possible protective effects of tea consumption against stone formation in postmenopausal women include additional water intake, the diuretic effects of caffeine, and the presence of antioxidant components (Barghouthy et al., 2021a). In addition, differences in urine composition compared to premenopausal women may be associated with a higher risk of developing of KSD (Prochaska, Taylor & Curhan, 2018). Metabolic syndrome has also been reported to be more prevalent in postmenopausal women than in premenopausal women (Park et al., 2003), and metabolic syndrome has been strongly associated with an increased risk of KSD (Chang et al., 2021). Several mechanisms have been proposed for the effect of green tea, including decreased absorption of lipids and activated AMP-activated protein kinase, thereby reducing metabolic syndrome parameters (Yang et al., 2016). This may be another explanation for the association between tea consumption and a lower incidence of KSD in postmenopausal women.

This is the first large-scale longitudinal population-based study to report a strong association between habitual tea drinking and a reduction in the prevalence of KSD in postmenopausal women. Despite these strengths, there are also some limitations to the current study. First, self-reported KSD is the major limitation, even though the participants answered the questions during follow-up interviews to ensure consistency of the responses. KSD in the participants could have been confirmed with computed tomography to reduce bias. In addition, previous similar studies have used self-reported KSD questionnaires (Shoag et al., 2019; West et al., 2008). Second, we did not measure the maximum amount of tea consumption that effectively prevent the development of KSD, because some people may experience side effects related to the caffeine and tannin contents. Third, it is common to distinguish different types of tea according to how the tea leaf is fermented, and to use the classification of fully, semi- and non-fermented tea. However, there are still subtle different in each fermented group, based on the tea tree and place of origin. Fourth, we did not discuss women with early menopause, which seems to be another subgroup. Early menopause can occur naturally or be induced by some medical treatments such as surgery or chemotherapy. Fifth, we lacked information about stone types, but CaOx stones account for the majority of KSD in the Taiwanese population, followed by calcium phosphate, and uric acid stones (Chou et al., 2007). Sixth, we acknowledge that a limitation of our study is our focus solely on postmenopausal women, which restricts its applicability to a broader population. However, evidence from at least 14 studies, including one meta-analysis, indicates the protective effects of tea consumption on kidney stone risk in men and premenopausal women (Barghouthy et al., 2021b). Our aim was to provide new insights into this specific population rather than reiterate findings from groups where this topic has already been explored. By concentrating on postmenopausal women, our study seeks to address the unique factors that may influence kidney stone disease risk in this higher-risk group. Seventh, as this is a cross-sectional analysis, we only assessed the presence of KSD at the time of enrollment. The questionnaire asked whether participants had ever been diagnosed with KSD but did not specify whether the diagnosis occurred during pre- or post-menopause. Furthermore, as a cross-sectional study, we cannot establish causality and can only report associations. To address this, we conducted sensitivity analyses across different subgroups to provide a more precise understanding of the effects of tea consumption on KSD. Finally, a limitation of this study is the overlap in the postmenopausal women cohort with our previous publication (Tang et al., 2023). However, the two studies have distinctly different focuses and objectives. The previous study explored the association between menopause (pre- vs. post-menopausal) and KSD in a cohort of 17,460 women, assessing the impact of menopause on KSD risk. In contrast, the current study focuses solely on postmenopausal women (11,484 women) and investigates the relationship between habitual tea consumption and the prevalence of KSD. The target variables, population subgroups, and research questions are different. Despite the overlapping dataset, the hypotheses and findings in this study are novel and provide valuable insights into tea consumption and KSD risk, which were not explored in our previous work.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study highlights that habitual tea consumption may be linked to a lower prevalence of KSD among postmenopausal women. With a significant reduction in risk observed among those who regularly consume tea, our findings underscore the potential protective role of tea in this vulnerable population. Given the increasing incidence of KSD in postmenopausal women, it is crucial to further investigate the underlying mechanisms by which tea may exert its protective effects. Future research should focus on elucidating the specific compounds in tea that contribute to this reduction in risk, as well as conducting longitudinal studies to confirm these associations and explore the optimal amount and type of tea for kidney health.

Supplemental Information

Raw data.

The medical records, behaviors, and blood exam data from participants, enabling researchers to identify associations between personal behavior and diseases.